There exists a quiet ritual in the world of fine wine, a practice both revered and debated with near-religious fervor. It is the act of decanting. To the uninitiated, it might seem like a purely theatrical performance, an elaborate pouring of wine from one vessel to another. But for the connoisseur, it is a crucial alchemical process, a deliberate unlocking of a wine's deepest secrets. At its heart, decanting is a dance with oxygen, a carefully managed oxidation reaction that can transform a tight, brooding liquid into a symphony of aromas and flavors. This is the story of that transformation, the science and the soul behind letting a wine breathe.

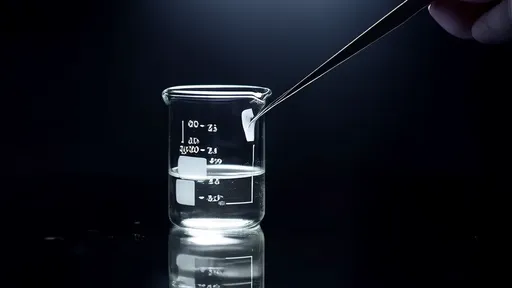

The fundamental force at play when you uncork a bottle and pour its contents into a decanter is exposure to air, specifically the oxygen within it. Wine, particularly a young, tannic red or a tightly wound white, can be a closed book upon opening. Its compounds are bound up, its aromas muted, its structure often harsh and astringent. The primary goal of decanting is to accelerate the very slow process of oxidation that would eventually happen in the bottle over years, condensing it into a matter of minutes or hours. This controlled exposure triggers a series of chemical reactions that are nothing short of miraculous for the wine's character.

One of the most significant changes involves the management of tannins. These phenolic compounds, derived from grape skins, seeds, and stems, are crucial for a wine's structure and aging potential. However, in their youth, they can be aggressive, causing a drying, puckering sensation on the palate. When oxygen is introduced, it begins to soften these tannic chains. The molecules start to polymerize, linking together to form longer, smoother chains. This process doesn't eliminate the tannins; it refines them. The harsh, gritty edge is polished away, revealing a wine with a supple, velvety texture that feels integrated and harmonious rather than abrasive.

Simultaneously, a parallel reaction is occurring with the wine's aromatic compounds, or esters. Many of the complex fruity, floral, and spicy notes we adore in wine are volatile compounds trapped in a reduced state immediately after opening. The introduction of oxygen acts as a catalyst, volatilizing these compounds and carrying them to your nose. It's like opening a window in a stuffy room. A wine that initially smelled of little more than alcohol and primary fruit might, after some time in a decanter, suddenly burst forth with layers of scent: ripe blackberries, violets, vanilla, tobacco, and earth. This is the "bloom" or "awakening" that enthusiasts speak of—the moment a wine truly finds its voice and sings.

Furthermore, decanting serves a practical, albeit less glamorous, purpose: the separation of sediment. Older red wines, particularly those bottled without filtration, often throw a deposit of tannins and color pigments over time. This sediment is a natural byproduct of aging and is completely harmless, but it is bitter and gritty, detracting from the wine's clarity and pleasure. By pouring the wine steadily and gracefully into a decanter, leaving the last ounce with the sediment in the original bottle, one achieves a crystal-clear pour. This act of clarification ensures that every sip is visually appealing and free from any textural unpleasantness, allowing the pure, evolved character of the mature wine to shine through unimpeded.

Yet, decanting is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Its application requires discernment. A fragile, forty-year-old Burgundy might need only twenty minutes in a decanter to open up, and any more would cause its delicate bouquet to evaporate into nothingness—a phenomenon known as oxidation in the negative sense, where the wine loses its fruit and becomes flat and vinous. Conversely, a powerful, young Barolo or Cabernet Sauvignon might demand two, three, or even more hours to unwind its tightly coiled structure. The shape of the decanter itself plays a role; a vessel with a wide base maximizes the surface area of wine exposed to air, accelerating the process significantly.

The debate around decanting even extends to white wines. While less common, many full-bodied, oak-aged whites like White Burgundy or oaked Chardonnay can benefit tremendously from a brief decanting. It helps to integrate the oak-derived flavors, soften any sharp acidity, and promote a richer, more rounded mouthfeel. The key, as always, is timing and intention. It's about listening to the wine and understanding what it needs to express its fullest self.

In the end, the act of decanting is a bridge between the winemaker's art and the drinker's experience. It is a gesture of patience and respect for the liquid in the glass. It acknowledges that a great wine is a living, evolving entity. By facilitating this controlled oxidation, we are not merely aerating a beverage; we are participating in its final stage of maturation. We are coaxing out nuances that the winemaker embedded years ago, waiting for this very moment. The burst of flavor, the softening of texture, the unveiling of hidden aromas—this is the flavor eruption, the glorious payoff for those willing to wait. It transforms the simple act of drinking into an experience, a conversation with the wine that is as deep and complex as the decanter itself.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025