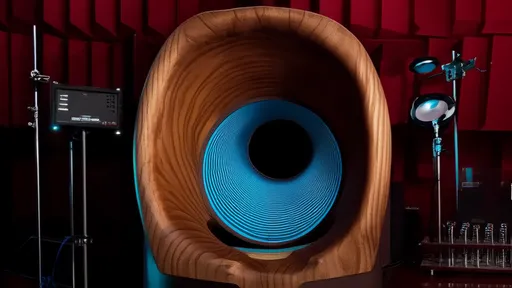

In the hushed stillness of a recording studio, a new kind of archive is being built. It is not filled with the familiar sounds of music or spoken word, but with the subtle, rhythmic whispers of life itself. This is the world of Heartbeat Recording Studio, a pioneering initiative dedicated to the archival of biological acoustics—the sounds of living organisms, captured and preserved as a unique form of memory. The project, situated at the intersection of art, science, and technology, seeks to create a living library of heartbeats, breaths, and other internal symphonies, offering a profound new way to document and remember life in all its forms.

The concept is as simple as it is revolutionary. Using highly sensitive, non-invasive acoustic sensors, the studio records the internal sounds of various creatures—from the frantic flutter of a hummingbird’s heart to the slow, deep pulse of a blue whale, or even the gentle thrum of a human heartbeat at rest. These recordings are not merely stored as data files; they are treated with the care and reverence of archival artifacts. Each recording is meticulously cleaned, annotated with contextual metadata—such as the subject’s species, age, health status, and emotional state—and saved in multiple high-resolution formats to ensure longevity. The resulting collection is a biodiverse soundscape, a frozen moment of acoustic life that can be revisited and studied for generations to come.

But why archive a heartbeat? The founders of the project argue that biological sounds are among the most intimate and immediate records of existence. “A heartbeat is a story,” says Dr. Aris Thorne, a bioacoustician and lead researcher on the project. “It tells us about stress, joy, health, and fatigue. It changes with age, with environment, with experience. In many ways, it is a non-verbal diary of a life.” This perspective transforms the archive from a mere scientific repository into a deeply humanistic—and indeed, a more-than-human—enterprise. It is about preserving not just the fact of life, but the feeling of it. The quiet, steady pulse of a sleeping child, the racing drumbeat of a predator on the hunt, the final, fading rhythm of an elderly elephant—these are narratives written in rhythm and frequency, waiting to be heard.

The technological backbone of the Heartbeat Recording Studio is a marvel of modern engineering. To capture these often faint and complex internal sounds without causing distress to the subjects, the team employs laser vibrometers and piezoelectric sensors that can detect vibrations through surfaces or even at a distance. This allows them to record animals in zoos, sanctuaries, and even the wild with minimal intrusion. The raw recordings are then processed through advanced algorithms that filter out ambient noise—like wind or distant human activity—to isolate the pure biological sound. The goal is fidelity: to preserve these acoustic signatures with as much clarity and depth as if the listener were standing right beside the creature, ear pressed against its hide or shell.

Beyond pure archival, the project has sparked unexpected applications. Medical researchers have begun collaborating with the studio, using its growing library of human heartbeats to train AI models for early diagnosis of cardiac conditions. The subtle variations in rhythm and sound that might be imperceptible to a human ear can be flagged by machine learning algorithms, potentially leading to breakthroughs in non-invasive diagnostics. Meanwhile, artists and composers are using the sounds as source material for new works, creating symphonies that weave together the heartbeats of hundreds of different species into a haunting chorus of planetary life.

Perhaps the most poignant dimension of the archive is its role in conservation and memory. For endangered species, the heartbeat recording becomes a kind of acoustic portrait—a way to remember an individual animal, or even an entire species, should they vanish from the earth. The studio has partnered with conservation groups worldwide to record animals like the northern white rhinoceros, of which only two females remain. The heartbeat of a species on the brink of extinction is a powerful, emotional artifact. It is a sound that speaks of fragility, resilience, and loss. It is a memory made tangible, a voice preserved against silence.

Ethical considerations are, of course, paramount. The team operates under a strict protocol to ensure that no animal is harmed, stressed, or unduly disturbed during recording. Sessions are kept short, and animal behavior is constantly monitored by ethologists. For human participants, consent is explicitly obtained, and recordings are often anonymized unless otherwise specified. The project raises fascinating questions about what it means to “own” one’s biological sound. Is your heartbeat yours to keep, or does it become part of a shared acoustic commons once it is recorded? These are questions the team grapples with as the archive grows.

Looking to the future, the Heartbeat Recording Studio aims to expand its collection into the millions of recordings, creating a comprehensive acoustic atlas of life on Earth. There are plans for virtual reality experiences, allowing people to “step inside” the soundscape of a forest or ocean, hearing the layered heartbeats of its inhabitants. There is also a contemplative, almost spiritual aspect to the work. In a world increasingly dominated by visual media and digital noise, the archive invites us to listen deeply—to reconnect with the primal, rhythmic truths that underlie all life.

In the end, the Heartbeat Recording Studio is more than a scientific project; it is a philosophical statement. It asserts that life is worth listening to. That memory can be held in a vibration. That long after we are gone, the echo of a heartbeat—steady, stubborn, alive—might remain, telling a story that otherwise would have been lost to time. It is an archive of presence, written in the oldest language of all: the sound of being here.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025