The diamond industry stands at the precipice of a transformative era, one defined not by the extraction of precious stones from the earth, but by their meticulous creation in controlled laboratory environments. For decades, the narrative of lab-grown diamonds was one of two competing technologies: Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) and High-Pressure High-Temperature (HPHT). Each method carved its own path, with distinct advantages and inherent limitations. CVD excelled in producing high-purity, type IIa diamonds ideal for jewelry, while HPHT was the workhorse for creating smaller, often colored stones and indispensable industrial grit. However, the most significant and exciting evolution is no longer a story of competition, but of convergence. The strategic fusion of CVD and HPHT technologies is emerging as the definitive next chapter, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in lab-grown diamond synthesis and unlocking unprecedented levels of quality, size, and efficiency.

The foundational principles of each technology are what make their combination so powerful. The HPHT method seeks to replicate the extreme conditions found deep within the Earth's mantle. A small diamond seed is placed within a sophisticated press and subjected to immense pressures exceeding 1.5 million pounds per square inch and scorching temperatures around 1,500 degrees Celsius. In this crucible, a carbon source, typically graphite, dissolves in a molten metal flux and crystallizes onto the seed, gradually building a diamond crystal. The process is renowned for its efficiency and ability to produce diamonds with certain desirable characteristics, but it can also introduce metallic inclusions and often results in crystals with a cuboctahedral shape that requires significant cutting and polishing, leading to higher material loss.

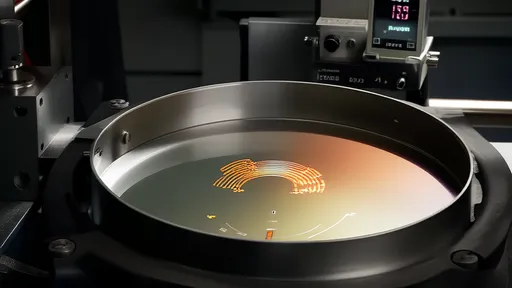

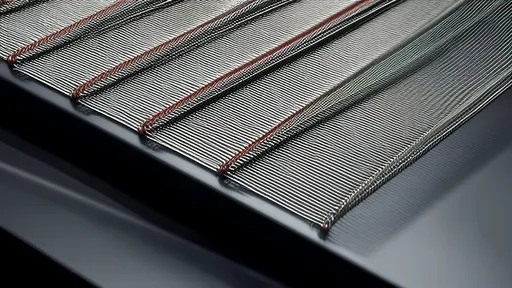

In contrast, the CVD process operates on a fundamentally different principle. It takes place inside a vacuum chamber filled with a carbon-rich gas, most commonly methane, mixed with hydrogen. By introducing microwave energy, the gas is ionized into a plasma, breaking down the molecular bonds and freeing carbon atoms. These atoms then rain down and settle on a flat diamond seed plate, building the diamond layer by atomic layer in a process that more closely resembles 3D printing. CVD allows for exceptional control over the diamond's purity and can produce larger, flatter plates that are more conducive to cutting larger gemstones. Its primary historical challenge has been managing internal strain and avoiding the formation of non-diamond carbon, which can impart a brownish hue to the crystal.

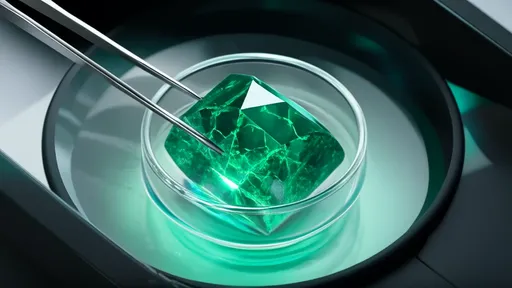

The limitations of each standalone process have become the catalyst for innovation. Producers seeking to create large, flawless, colorless diamonds for the high-end jewelry market found that relying solely on one method presented hurdles. A CVD-grown diamond might be large and pure but could retain a subtle strain or brown tint that required post-growth treatment to achieve a D-flawless grade. An HPHT diamond might grow quickly but could contain inclusions that made it unsuitable for a premium solitaire. The industry's answer was not to choose one, but to use them in concert. This hybrid approach leverages the unique strengths of each technology at different stages of the growth process, creating a synergistic effect that is greater than the sum of its parts.

The most prevalent hybrid model involves using HPHT-grown diamonds as superior seeds for the CVD process. Not all diamond seeds are created equal. Traditionally, CVD processes used thin slices of natural diamond or previously grown CVD material as seeds. However, these seeds can have defects, impurities, or internal grain boundaries that propagate through the entire new layer of CVD growth, limiting the ultimate size and quality of the final crystal. By utilizing a high-quality, type IIa HPHT crystal as the seed, growers provide a pristine, perfectly structured foundation. This superior starting point allows the subsequent CVD layer to grow with fewer defects and less intrinsic stress, enabling the production of larger, more perfect single-crystal diamonds. The HPHT seed acts as a perfect template, guiding the carbon deposition into a more orderly and flawless structure.

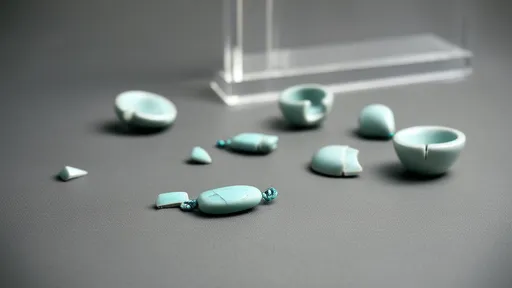

Another powerful application of this technological fusion is in post-growth treatment and enhancement. As mentioned, CVD diamonds can sometimes emerge from the chamber with a brownish coloration due to crystal lattice defects or the presence of vacancy clusters (missing carbon atoms). These stones, while structurally sound, lack the optical brilliance demanded by the jewelry market. Here, HPHT technology is deployed not for growth, but for healing. By subjecting these brown-tinted CVD diamonds to a short, carefully calibrated HPHT cycle—a process often called annealing or pressing—the intense heat and pressure can effectively "mend" the crystal lattice. Vacancies are eliminated, and the diamond's structure is relaxed, transforming its color from brown to a spectacular colorless or near-colorless grade. This post-growth treatment has become an industry standard for maximizing the yield of high-quality gemstones from the CVD process.

Looking toward the future, the trajectory points toward even deeper integration, moving beyond a simple two-step process. The next frontier is the development of truly unified hybrid reactors. Research and development are focused on creating a single, advanced growth chamber capable of dynamically switching between or simultaneously applying CVD and HPHT conditions. Imagine a reactor that begins with an HPHT phase to establish a perfect core crystal structure and then seamlessly transitions to a CVD phase to add bulk with precise chemical control, all without ever removing the diamond from its controlled environment. This would eliminate handling and contamination risks while allowing for real-time optimization of the growth parameters. Such a machine would represent the ultimate synthesis of these two powerful technologies, offering growers an unparalleled tool for crafting diamonds to exact specifications for both gemological and technological applications.

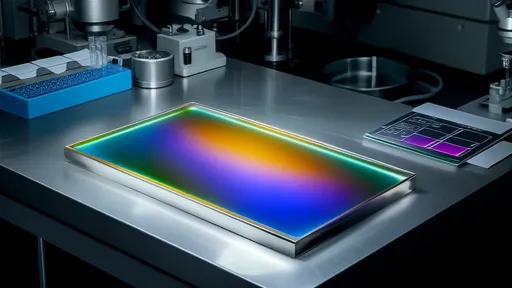

The implications of this technological convergence extend far beyond the jewelry counter. While creating larger, more perfect gemstones is a primary driver, the hybrid approach is a boon for advanced technological applications. The semiconductor and quantum computing industries require ultra-pure, single-crystal diamond wafers with specific electronic properties. The combined CVD-HPHT process is the only method capable of producing such material at the required scale and quality. By starting with a flawless HPHT seed and using CVD to grow a thick, ultra-pure layer, manufacturers can create the perfect substrate for next-generation electronics. This synergy ensures the material has both the crystalline perfection from the seed and the chemical purity achievable through CVD, making it ideal for high-power electronics, radiation detectors, and quantum sensors.

In conclusion, the lab-grown diamond sector is undergoing a profound paradigm shift. The historical dichotomy between CVD and HPHT is giving way to a new era of collaborative innovation. The fusion of these technologies is not merely a technical footnote; it is the central driving force behind the industry's rapid advancement. By harnessing the brute-force efficiency of HPHT to create perfect foundations and the precise, layer-by-layer control of CVD to build upon them, scientists and manufacturers are overcoming the inherent limitations of each standalone method. This hybrid approach is setting a new benchmark for quality, enabling the reliable production of large, colorless, and flawless diamonds that were once unimaginable. It is a testament to human ingenuity, demonstrating that the future of diamond growth lies not in choosing one path over another, but in brilliantly combining them to unlock a new world of possibility.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025