In the intricate world of enamel artistry, the kiln stands as both a crucible of creation and a master of transformation. Within its heated chamber, the marriage of metal and glass unfolds under the precise governance of temperature—a variable so potent that each minute within the firing cycle wields decisive influence over the final chromatic outcome. For artisans and industrial craftsmen alike, understanding the thermal narrative of enameling is not merely technical knowledge; it is the language through which color speaks, evolves, and achieves permanence.

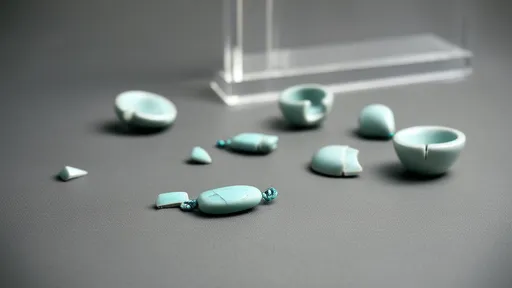

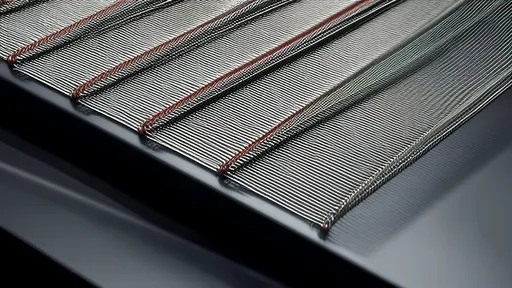

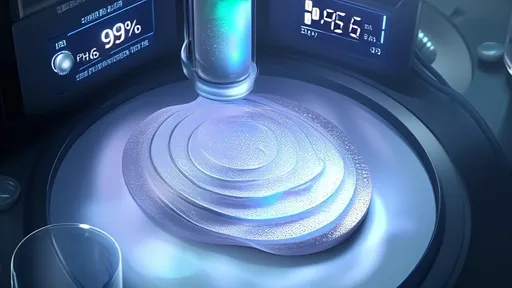

The journey begins with the application of finely ground glass particles, mixed into a paste or dusted onto a prepared metal surface. These particles, inherently transparent or opacified, contain metallic oxides that promise color—but only through the alchemy of heat will that promise be fulfilled. As the kiln door closes and the temperature begins its ascent, a silent, critical dialogue between heat and material commences. The first few minutes are often gentle, a slow ramp-up designed to drive off moisture and burn away organic binders without causing thermal shock. During this phase, the enamel particles remain largely unchanged in hue, but their physical structure prepares for fusion.

As the kiln crosses the threshold of approximately 750°F (400°C), the real transformation initiates. The glass particles start to soften, their surfaces becoming tacky. It is here that the initial color development can be observed—a subtle deepening or shifting as the oxides begin to react. Cobalt blues might start to show their first true notes, while iron-based reds begin to awaken from their dull, powdered state. This period is delicate; too rapid a temperature increase can trap gases or cause bubbling, leading to pitted surfaces and compromised color clarity. The artisan must read the kiln’s behavior, understanding that each minute of exposure within this range sets the foundation for chromatic integrity.

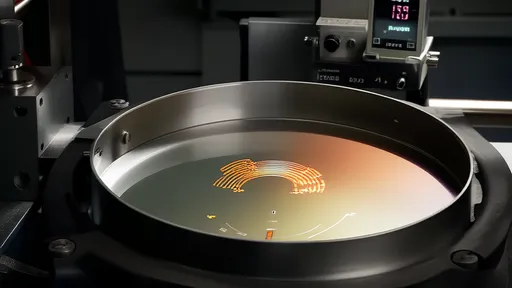

The heart of the firing process occurs as the kiln approaches and sustains its peak temperature, typically between 1400°F and 1600°F (760°C to 870°C) for most vitreous enamels. This is the stage where time becomes unequivocally decisive. The duration at peak heat—sometimes varying by mere minutes—directly dictates color saturation, value, and even hue shift. For instance, a copper-rich red enamel held at 1470°F for three minutes may emerge a bright, vermilion-like shade, while an additional two minutes could drive it toward a deeper, maroon tone. The chemistry is precise: prolonged heat allows for greater migration and interaction of metal ions within the molten glass matrix, altering light absorption and reflection properties.

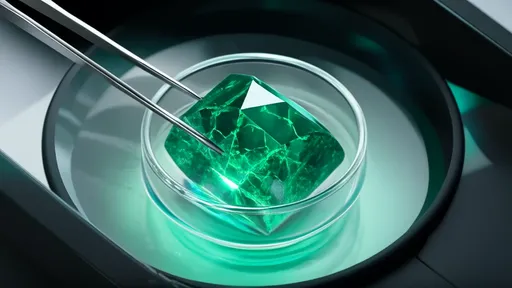

Similarly, yellows derived from antimony or lead-tin compounds are notoriously sensitive to over-firing. A minute too long in the high heat can cause them to dull, brown, or even decompose, losing their sunny brilliance. Conversely, some colors, like those from chromium oxides (greens), become more stable and vibrant with slightly extended firing times. The artist’s expertise lies in knowing not just the recipe, but the thermal personality of each pigment—how it responds to time at temperature, how it interacts with underlying layers or adjacent colors, and how it behaves on different metals, be it copper, silver, or gold.

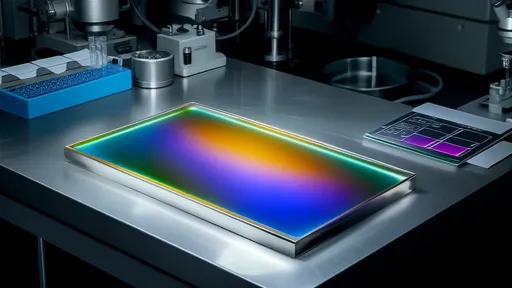

The cooling phase, often overlooked, is equally critical. Once the kiln is shut off, the descent in temperature must be controlled to prevent devitrification—the crystallization of the glass that can cause cloudiness—or cracking due to differing thermal contraction rates between metal and enamel. Slow, gradual cooling allows the glass to anneal, stabilizing the color and ensuring its durability. Rapid quenching might lock in certain hues but at the risk of structural weakness. During this period, some colors continue to evolve; for example, certain pink shades achieved with gold chloride may only fully develop their blush as they cool through specific temperature ranges, a phenomenon watched with anxious anticipation by the enamelist.

Modern kilns equipped with digital controllers allow for precise programming of ramp, soak, and cool rates, enabling reproducibility unheard of in ancient times. Yet, even with technology, the artisan must account for variables—kiln calibration, ambient humidity, the thickness of application, and the specific batch of enamel. It is a dance of science and sensation, where each firing is a unique performance. Master enamelists often keep detailed logs, correlating time-temperature curves with visual outcomes, building a personal database of thermal wisdom.

In industrial applications, where consistency across thousands of pieces is paramount, the temperature curve is rigorously standardized. However, even here, minute adjustments are made to compensate for material lot variations or desired aesthetic tweaks. The difference between a signature brand color and a rejected batch can be a matter of seconds at a critical temperature point.

Ultimately, the kiln’s temperature curve is the invisible hand that guides enamel from potential to permanence. Each minute within its realm is a stroke on the canvas of color, a decisive influence that transforms powdered glass into lasting beauty. For those who practice this ancient craft, respect for the kiln’s power and patience with its timeline are not just skills—they are the essence of creating art that endures.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025